☕️ Coffee & Covid ☙ Tuesday, September 21, 2021 ☙ Closing Argument 🦠

In a special edition, I present my complete closing argument in my case seeking to enjoin a city's vaccine mandate.

Good morning C&C family. Today I bring you a very special edition — my complete closing argument from the injunction hearing in Friend v. City of Gainesville. In the case, I am asking the court to enjoin — restrain — the city from enforcing its vaccine mandate on its employees, including firefighters, cops, electrical lineworkers, wastewater engineers, utility crews, and city employees of every description. We have 250 individual plaintiffs, of whom 201 are already named in the case caption.

The judge didn’t rule on the injunction at the close of the hearing, but rather asked for competing proposed orders by noon today. We’ll have a strong proposed order submitted by then for her to consider. In the meantime, you can see the details here, details that Google is already scrubbing from the Internet. I hope you enjoy it, even the legal parts!

FRIEND VS. CITY OF GAINESVILLE

Alachua County Circuit Court 2021-CA-2412

PLAINTIFFS’ CLOSING ARGUMENT

May it please the Court.

The Plaintiffs are asking the Court to immediately enjoin the City’s new vaccination requirement until their claims can be tried.

I’m going to divide my argument into two parts.

In part one, I’ll frame the issue to be decided.

In part two, I’ll explain the simple, straightforward five-step legal analysis that requires this Court to grant the Plaintiffs’ injunction — today. It’s not even close.

I will now begin addressing part one.

PART ONE — THE CITY’S PROPERTY RIGHTS

The City thinks that its employees’ bodies are its property. And since the City can do whatever it wants with its property, it can do whatever it wants with its employees’ bodies.

Farmers routinely fully vaccinate their herds of farm animals. It’s a commercial necessity. You can’t have some of those animals getting sick or even spreading disease around the herd. Those animals are valuable. They cost money. You can’t afford to lose a few to some cow virus or something.

The reason that kind of herd vaccination is uncontroversial is because the farmer owns the cows. Those cows are the farmer’s property. He can do what he wants with his property. Those cows don’t have any right to bodily autonomy. Right up to and including death. Their bodies are the farmer’s property. He can inject anything he wants to into them.

The City owns buildings that have air conditioning systems. If a new ultra-violet technology comes out, the City can install it into their HVAC systems if it wants to, whenever it wants to. Nobody’s going to complain about that. The HVAC systems are the City’s property. Those ultra-violet lights might kill germs and save the City some money by reducing sick days or something.

Now there’s a new vaccine technology. The City wants to install the new vaccine technology into its employees — just like it can install ultra-violet lights into its HVAC systems — because they are its property. It can do what it wants with its property. Especially if it saves money.

Does this sound hyperbolic? It’s not. The City makes this argument throughout its opposition brief. The City even says in its brief that, while it’s crass, the justification that overrides all arguments would be some unquantified and unquantifiable savings to its self-insurance plan.

We need look no further than the capstone of the City’s opposition, its concluding sentence. The sentence that summarizes and encapsulates the City’s entire previous argument. Let me read you what it says:

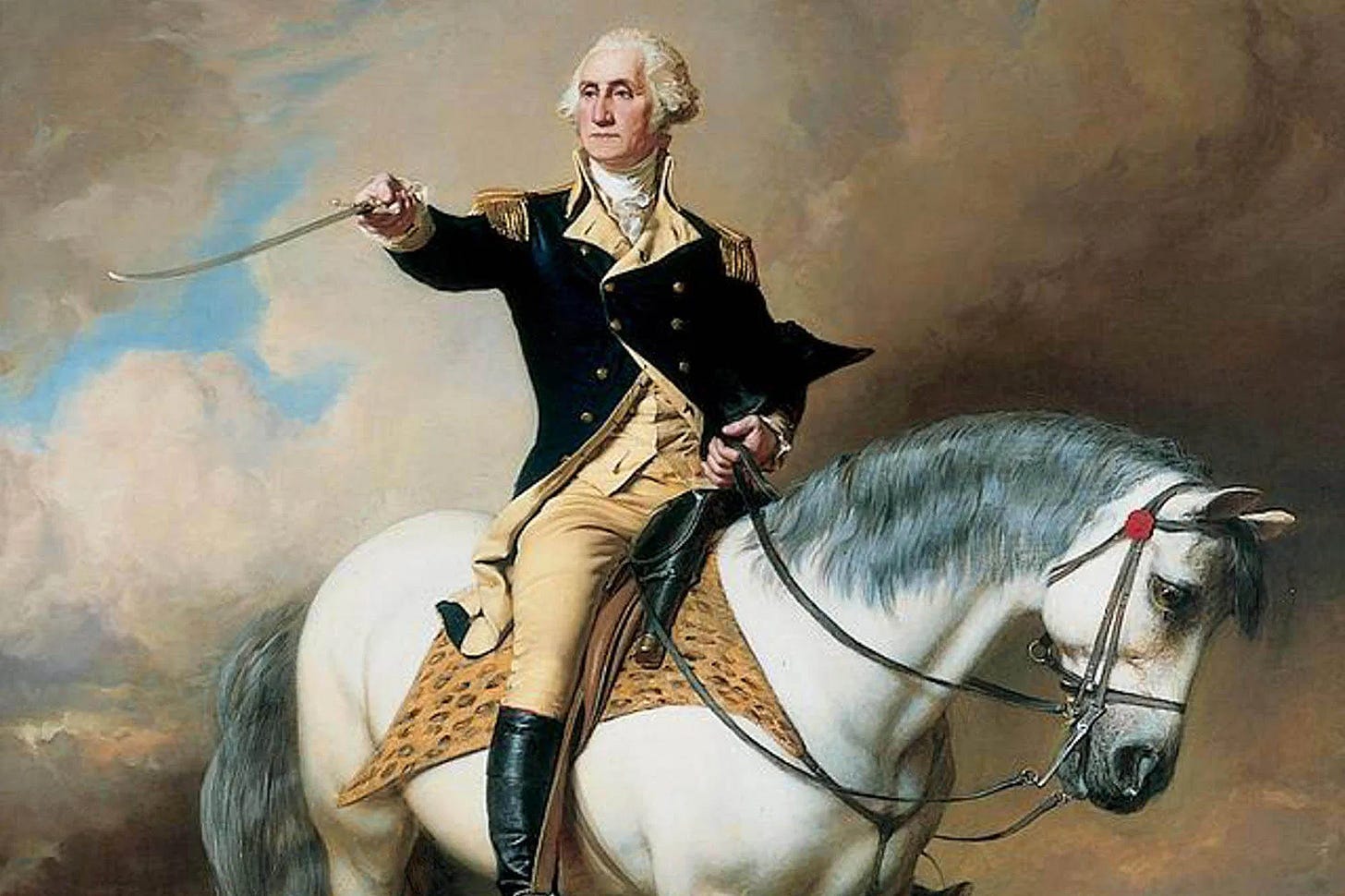

In the words of George Washington, upon ordering the mandatory smallpox inoculation of colonial troops in 1777, “Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure, for should the disorder infect the Army in the natural way and rage with its usual virulence we should have more to dread from it than from the Sword of the Enemy.”

George Washington. Your first thought, like mine, is that the City has a pretty high opinion of itself. It thinks it is just like our first president, George Washington, the brilliant general who won the Revolutionary War.

But once I started thinking about it some more, I realized, the City is right. It is like George Washington. George Washington in 1777, just like the City said in its brief. So here are a few things you probably didn’t remember — like I didn’t — about George Washington in 1777.

In 1777, George Washington was the supreme commander in chief of the continental army, which was then fighting the British. That was eleven years before we had a Constitution, which wasn’t ratified until 11 years later in 1788.

1777 was also eleven years before we had a Supreme Court.

1777 was also ten years before we even had a president.

See what the City is saying? They think they’re like George Washington — a supreme military commander — in 1777 — a decade before the US even had a Constitution or a court to argue about it in.

In other words, the City thinks it is just as free from pesky constitutions as George Washington was in 1777, when he was ordering all those soldiers to get a primitive form of vaccination, right before ordering them to charge up the hill into oncoming musket fire.

The City thinks it’s George Washington.

I thought about it some more. Do we have any idea what George Washington might have thought about issues like bodily autonomy? And I realized that yes, we do have some idea. We know exactly what the City’s avatar, George Washington, thought about bodily autonomy.

I don’t mean this to be critical. George Washington lived in a different time, with different cultural norms. But George Washington owned people. He inherited his first ten people when he was eleven years old, and went on to buy and own hundreds more. He grew up with the idea that people could own people and do whatever they wanted with them. His employees were his property. They had no bodily autonomy. What a silly idea. He owned their bodies. Later in life, he even took their teeth to make his own dentures. Their bodies were his property.

George Washington looked at his employees as being the same as farm animals. You had your herd of farm animals, and you had your herd of employees. You had to manage those herds. You had to keep them healthy. You had to vaccinate them.

You don’t ask the herd how it feels about being vaccinated. Herds are just dumb animals who don’t know what’s good for them. You have to make your herds get vaccinated. Compel them, in other words.

Now, the City is going to rush to argue, hey, we’re not making anybody do anything outside of work. This is just a work thing. It’s an on-the-job requirement, just like wearing a uniform. You want to work here? You have to wear a City of Gainesville polo shirt at work. It’s exactly like that.

And that is exactly what George Washington would say.

But the City’s argument is nonsense. It’s nonsense because you can take the polo shirt off when you go home. But you can’t take the vaccine off! Because it is making permanent changes to employees’ bodies. Changes that endure beyond the workplace. All the way beyond. Changes that follow the employees into their homes and their private lives. Changes that follow the employees to the next place of their employment, and ultimately, to the grave.

In his lengthy dissent in Green, Judge Lewis made this very point, as he was discussing the temporary nature of compelled mask wearing. You only have to wear the masks at work. Judge Lewis said:

The fact that the mask mandate does not infringe on a person’s private or home life further indicates that it does not implicate Florida’s right of privacy. … Florida’s right of privacy guarantees the freedom of a person to control his own body…

Unlike the mask mandate at issue in Green, which Judge Lewis firmly felt did not interfere with a person’s private or home life, the City’s vaccine mandate absolutely does interfere with an employee’s private and home life. Of course it does. So, listen to what Judge Lewis said next:

The mask mandate is not compelled medical treatment, and the wearing of facial covering does not alter one’s physical person. Rather, the mask mandate is a temporary and de minimus interferencewith a person’s public interactions…

Well. Judge Lewis couldn’t have said it any better. He said the mask mandate is just a “temporary interference” when you’re in public. It’s not like it’s compelled medical treatment or anything. Then Judge Lewis made sure to point out the inescapable truth that face masks don’t alter one’s physical person. But vaccines do. They alter employees’ physical person. By definition.

So, what are we to make of the City’s argument that, hey, we aren’t bound by the constitution? The City says, we can do what we want with our employees. Our property.

It’s a pretty simplistic argument. In 1777, George Washington wasn’t bound by a constitution. The City thinks — wrote in its brief — that it’s like George Washington. So the City isn’t bound by a constitution either.

The City thinks it is has the authority of a pre-constitutional supreme military commander. Remember: one possible side effect of the vaccines, however rare, is death. Just like George Washington could order his soldiers to their deaths, the City believes it can require its employees to potentially take one for the team. Come on, be a team player. You know. You can’t make an omelet, and so forth.

George Washington didn’t respect bodily autonomy. He thought his employees were property. The City doesn’t res`pect bodily autonomy either, and it also thinks its employees are its property.

But — fortunately — Florida law says NO.

PART II — THIS COURT MUST IMMEDIATELY GRANT THE INJUNCTION

What I’d like to do here in Part II of my argument is briefly describe the five assertions that prove beyond argument that this Court must immediately grant the injunction, and then I’ll circle back and discuss the law related to each of the five sections in further detail.

Assertion One: The United States Supreme Court directs lower courts to test a compelled vaccination law against the constitution of the individual state. Jacobson.

Assertion Two: Compelling an unwanted "medical treatment" violates Florida's right to privacy — Article I, § 23 of the Florida constitution — and citizens’ right to refuse unwanted medical treatment. Browning, Green, Green(Lewis, J. dissent), and Macovech.

Assertion Three: If a challenged law merely implicates Florida's right to privacy, the burden automatically shifts to the government “to prove that the law furthers a compelling state interest in the least restrictive way”—also known as the “strict scrutiny” standard. Green and Gainesville Woman Care.

Assertion Four: The high “strict scrutiny” standard applies equally when the government enforces laws, and for “government action” “as an employer” to enforce a workplace policy. Kurtz.

Assertion Five: The vaccine mandate is presumptively unconstitutional because it violates Florida’s constitution. The city offered no witnesses or evidence to overcome this presumption. An injunction barring the vaccine mandate must issue as a matter of law. Gainesville Woman Care.

Let’s look at those assertions, one by one.

Assertion One — State Law Governs Compelled Vaccination

As I mentioned before, the City relied heavily on Jacobson in its brief. The City probably shouldn’t have brought up Jacobson, because the case helps the Plaintiffs, not the City. It could not be more clear: Jacobson holds that state lawgoverns compelled vaccination. In that case, the Court was considering a $5 fine on Massachusetts citizens who refused a compulsory smallpox vaccine.

But even Massachusetts wasn’t compelling anybody to take the vaccine. You just had to pay a small fine if you didn’t take it. You could opt-out by paying a minor ticket. They weren’t holding anybody down and sticking needles into them or anything.

And they sure weren’t terminating people’s employment, deleting their retirement benefits, and destroying their livelihoods.

But anyway, somebody sued over that $5 fine and took it all the way up.

And the United States Supreme Court said:

[T]his court … has distinctly recognized the authority of a state to enact quarantine laws and ‘health laws of every description’[.]

The mode or manner in which those results are to be accomplished is within the discretion of the state[.]

Then, the Supreme Court looked at Massachusetts’ state constitution, and discovered law that authorized the fine for rejecting a compelled medical treatment. Massachusetts didn’t have an explicit right of privacy in its constitution. Still doesn’t.

Jacobson says you must look to state law.

All right. The Supreme Court, applying the same Jacobson principles, would have come out the opposite way. Why? We come to the second assertion.

Assertion Two — The Right to Privacy

The majority in Green and the dissent didn’t agree on much. But they did agree on one thing: compelled medical treatments violate the Florida constitution. No question. It’s not even close.

Judge Lewis explicitly affirmed that Florida’s constitutional right to privacy includes the “right to … refuse medical treatment.”

So, the City was right about one thing. This case isn’t about the “right to stay unvaccinated.” This case is about a Floridian’s absolute right to refuse unwanted medical treatment. That’s what this case is about.

Judge Lewis isn’t the only judge who disagreed with the majority holding in Green, that mandatory masking is presumptively unconstitutional. Now, I think Green and Machovech can be reconciled. But, in a footnote, the majority in Green acknowledged the possibility of a split between the First DCA and the Fourth DCA in Macovech. And Judge Lewis cited Machovech fairly heavily for that case’s language about the masks in his dissent.

But you know what? Both Green and Macovech agree on one thing. Compelled medical treatments violate the right to privacy in the Florida constitution. Here’s how Macovech concluded:

Thus, requiring facial coverings to be worn in public is not primarily directed at treating a medical condition … As EO-12 does not implicate the constitutional right to choose or refuse medical treatment, the trial court correctly applied the rational basis standard of review to Appellants’ challenge to the ordinance. … Appellants’ sole argument on appeal fails because they did not establish that the … order mandating the wearing of face coverings intrudes on their constitutional right to refuse medical treatment.

So.

Anyway, it’s not just the First and the Fourth DCAs who explicitly recognized a right to refuse medical treatment. Our Supreme Court has also recognized that right, over and over. Here’s what the Florida Supreme Court said in the Browning case:

[E]veryone has a fundamental right to the sole control of his or her person. As Justice Cardozo noted seventy-six years ago:

Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body ...

An integral component of self-determination is the right to make choices pertaining to one's health, including the right to refuse unwanted medical treatment …

Recognizing that one has the inherent right to make choices about medical treatment, we necessarily conclude that this right encompasses all medical choices. A competent individual has the constitutional right to refuse medical treatment regardless of his or her medical condition.

Regardless of their condition. Regardless.

The bottom line is, citizens have the right to refuse unwanted medical treatments — regardless of their condition — under Article I, § 23 of the Florida constitution. And if the government punishes or discriminates against a citizen for accessing that right, in any way, the government violates the constitution.

So, what happens to the burden of proof when the right to refuse medical treatment comes into play? That’s Assertion Number Three.

Assertion Three — The Right to Privacy

If the right to refuse medical treatment comes into play, then citizen plaintiffs don’t have to prove anything to get an injunction. The citizen plaintiffs are presumed to be right. The burden shifts to the government, to prove it has met the high strict scrutiny standard, a standard that requires it to somehow prove the negative: that there are no other means less restrictive to further its compelling state interest.

Maybe in most situations, the plaintiffs would have to prove something. But Green — binding on this Court — says this about injunctions in privacy cases:

[T]he supreme court has said that the analysis is entirely different when a temporary injunction motion is based on a privacy challenge. … The right of privacy is a “fundamental” one, expressly protected by the Florida Constitution, and any law that implicates it “is presumptively unconstitutional,” such that it must be subject to strict scrutiny and justified as the least restrictive means to serve a compelling governmental interest. … A plaintiff does not bear a threshold evidentiary burden to establish that a law intrudes on his privacy right, and have it subjected to strict scrutiny, “if it is evident on the face of the law that it implicates this right.”

So it is clear that citizens have the right to refuse unwanted medical treatments, and if the government’s law invades that right, it is presumed to be wrong, and it has the burden of proving the negative and that it meets the very high strict scrutiny standard.

But the City didn’t try to prove anything today. Not strict scrutiny. Not even a rational basis. Nothing.

That means the City loses. If it doesn’t put on evidence, then it has failed to meet its burden and the injunction must issue as a matter of law. It’s happened before. It happened in the Gainesville Woman Care case, heavily cited in Green. In that case, the Supreme court said that because the government didn’t put on any evidence, it was game over:

It would make no sense to require a trial court to make factual findings regarding a state’s compelling interest, as the First District would require, when the State presented no evidence from which a trial court could make such findings.

So, why didn’t the City attempt to prove its “vaccinate or terminate” policy passes strict scrutiny? Because, it says, only citizens have constitutional rights, and — like pre-constitutional George Washington — the City doesn’t look at its property — I mean, its employees — as citizens. The City says that it can ignore the constitution, the Governor, the legislature, and the attorney general because it is a “corporation” — a “municipal corporation.”

But that’s not what the supreme court said.

Assertion Four — The Rights of Government Employees

There are really two parts to the City’s argument that it escapes constitutional scrutiny when it acts as an employer. The first part is that it should be treated the same as a private employer. Because private employers aren’t subject to constitutions, which after all, are limits on the government’s powers.

The second part of its argument is that the City says, hey, the “vaccinate or terminate” policy isn’t a law. It’s just a policy, expressly arguing that governments can escape constitutional limits by calling things “policies” instead of “laws.” In other words, executive actions independent from the legislature aren’t bound by constitutions since they aren’t laws.

But the Florida supreme court already handled these arguments in Kurtz.

So, in Kurtz the supreme court was reviewing the City of North Miami’s policy – not a law – of asking job applicants if they had smoke cigarettes within the prior twelve months. Somebody objected to that, and sued. The supreme court analyzed the city’s policy under Article I, § 23 of the Florida constitution. Listen to how the supreme court described the policy:

To reduce costs and to increase productivity, the City of North Miami adopted an employment policy designed to reduce the number of employees who smoke tobacco. In accordance with that policy decision, the City issued Administrative Regulation 1–46, which requires all job applicants to sign an affidavit stating that they have not used tobacco or tobacco products for at least one year immediately preceding their application for employment. … Once an applicant has been hired, the applicant is free to start or resume smoking at any time.

Reducing costs and increasing productivity. Sound familiar? It should — it is the same argument that the City of Gainesville is making.

But the point is, the supreme court analyzed the City of North Miami’s policy under the Florida constitutional right of privacy. It’s policy. Not a law.

But what about the argument that the constitution doesn’t apply to government when it acts as an employer? Listen to what the supreme court said in its very first footnote in that case:

Notably, because Florida's constitutional privacy provision applies only to government action, the provision would not be implicated if a job applicant was applying for a position with a private employer.

See that? The supreme court makes a clear distinction between a government employer and a private employer. It says the constitutional right to privacy wouldn’t be implicated for a private employer. But it IS implicated for a public employer.

The supreme court in Kurtz even found that employees can have even more constitutional protection once they’ve been hired by a government employer than they have as free citizens applying for government jobs. Listen to what the supreme court said:

Notably, we are not addressing the issue of whether an applicant, once hired, could be compelled by a government agency to stop smoking. Equally as important, neither are we holding today that a governmental entity can ask any type of information it chooses of prospective job applicants.

That seems pretty clear. Government employees still have rights even when the government is acting “as an employer.” Next, listen to how the supreme court described the analysis that MUST be undertaken when a government — acting as an employer — potentially invades a citizen’s right to privacy:

Thus, to determine whether Kurtz, as a job applicant, is entitled to protection under article I, section 23, we must first determine whether a governmental entity is intruding into an aspect of Kurtz's life in which she as a “legitimate expectation of privacy.” If we find in the affirmative, we must then look to whether a compelling interest exists to justify that intrusion and, if so, whether the least intrusive means is being used to accomplish the goal.

In Gainesville Woman Care,[1] the supreme court explicitly said that the right of privacy holds “regardless of the nature of the activity.” In other words, it doesn’t matter if it is government “acting as an employer” — citizens retain their fundamental rights:

[I]t is settled in Florida that each of the personal liberties enumerated in the Declaration of Rights is a fundamental right. Legislation intruding on a fundamental right is presumptively invalid and, where the right of privacy is concerned, must meet the “strict” scrutiny standard. Florida courts have consistently applied the “strict” scrutiny standard whenever the Right of Privacy Clause was implicated, regardless of the nature of the activity.

Gainesville Woman Care repeats the same proposition, holding that strict scrutiny applies to ANY LAW implicating the right of privacy:

This Court applies strict scrutiny to any law that implicates the fundamental right of privacy.

That even includes laws — or policies — by government agencies when acting as employers. There aren’t any exceptions. It doesn’t say “any law except when the government is acting as an employer.”

It says, any law.

In other words, the employees retain the rights to their own bodies. The City does not have any right to treat their bodies as property.

The City also argues that it’s just conditioning employment on vaccination; it’s not holding people down and giving them shots or anything. It doesn’t matter. It is hornbook law that public employees don’t have to choose between their constitutional rights and having a job. One case put it this way:

Because [Richmond Public Schools] recommends termination when an employee refuses urinalysis testing, Robertson had to choose between losing his job or submitting to the urinalysis test. That choice was not a choice at all.

Robertson v. Sch. Bd. of City of Richmond, Virginia, 2019 WL 5691946, at *8 (E.D. Va. 2019).

The Eleventh Circuit agreed, in a case cited by Robertson. It reiterated the same point:

Employees who must submit to a drug test or be fired are hardly acting voluntarily, free of either express or implied duress and coercion.

Am. Fed’n of State, County & Mun. Employees Council 79 v. Rick Scott, 717 F.3d 851, 874 (11th Cir. 2013).

In the Scott case, the court described the holding of a U.S. Supreme Court case like this:

… the government cannot require its employees to relinquish their Fifth Amendment rights on pain of termination because “[t]he option to lose their means of livelihood or to pay the penalty of self-incrimination” was “the antithesis of free choice.”

Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.S. 493 (1967).

We have already seen that all Florida courts agree: compelled medical treatments intrude into a citizen’s legitimate expectation of privacy. The conditioning of employment on a waiver of constitutional rights impairs those rights. Therefore, this Court must apply strict scrutiny to the City’s vaccine policy. It must.

Assertion Five — The Injunction Must Issue as a Matter of Law

We have seen that the vaccine mandate is presumptively unconstitutional because it violates Florida’s constitution.

Because the city offered no witnesses or evidence to overcome this presumption, the Court must issue an injunction barring the vaccine mandate, as a matter of law.

Green stated plainly that, when the government fails to put on evidence of its compelling state interest, it is game over. Here’s how Green, citing Gainesville Woman Care, put it:

When the government fails to offer evidence to demonstrate a compelling state interest, the trial court then is absolved of having to make any finding to that effect.

No findings are required.

Green also teaches that, after the court makes a threshold determination that the constitutional right of privacy is implicated, “the remaining prongs of the inquiry collapse into the first prong.”

That means that the Court must presume the elements necessary to obtain the injunction have been met: (1) that irreparable harm is likely; (2) that an adequate remedy at law is unavailable; (3) that public policy favors the injunction, and (4) that the plaintiffs are substantially likely to prevail on the merits.

Here’s the bottom line:

(1) Compelled medical treatments like vaccination policies violate the fundamental right to privacy

(2) Kurtz teaches that in Florida, at least, government employer policies are subject to the fundamental rights of privacy and bodily autonomy

(3) Therefore the burden shifted to the City to prove its policy meets strict scrutiny

(4) The City failed to offer evidence to demonstrate a compelling state interest

(5) The Court doesn’t have to make any findings

(6) The Court must presume that the elements necessary for the injunction have been met

The injunction should issue today. There’s nothing to think about. There’re no findings to be made. Absent evidence of a compelling state interest and use of the least restrictive means, and since it is clear under Kurtz that government is subject to the right of privacy even when acting “as an employer,” this is a very simple case.

I would like to incorporate the other arguments from our Reply, filed Friday, into this argument. Particularly the arguments about Florida’s Vaccine Passport Ban, which, as the Attorney General indicated in her Amicus, makes the City’s vaccine policy illegal by statute.

Judge, on behalf of my 250 clients, the plaintiffs, we are asking you to immediately issue the injunction.

Thank you.

[1]Gainesville Woman Care, LLC v. State, 210 So. 3d 1243, 1254 (Fla. 2017).

2 Timothy 1:7 "God does not give a spirit of fear, but love, power and a sound mind." Jeff clearly has a sound mind, and patriots everywhere should be sharing this and thanking him for his work.

So incredibly well-written, as usual! Praying for great results for you and your clients! Keep up the good work!