☕️ HABEAS CORPSES ☙ Monday, April 21, 2025 ☙ C&C NEWS 🦠

The judiciary melts down as twin stories of robed failure decorate the national narrative. One, ignored by legacy media, highlights the peril. The other, blanketed with coverage, shows the promise.

Good morning, C&C, it’s Monday! I hope everyone enjoyed a joyful and fulfilling holiday weekend. Today, we have two amazing stories, twin tales of double judicial meltdown. Let’s get after it.

🌍 WORLD NEWS AND COMMENTARY 🌍

👨⚖️👨⚖️👨⚖️

It wasn’t easy tracking down this eye-popping story, which combined all the elements of the immigration debate— yet corporate media still ignored it. The Albuquerque Journal ran the astonishing article last week below the bland, uninformative headline, “Doña Ana County judge resigns after feds arrest man at home.” It was an all-American story about a small-town judge, a quiet, well-kept house, a nice, peaceful neighborhood— but while the judge’s wife was in the kitchen cooking dinner, a designated terrorist was out back polishing a suppressed AR-15.

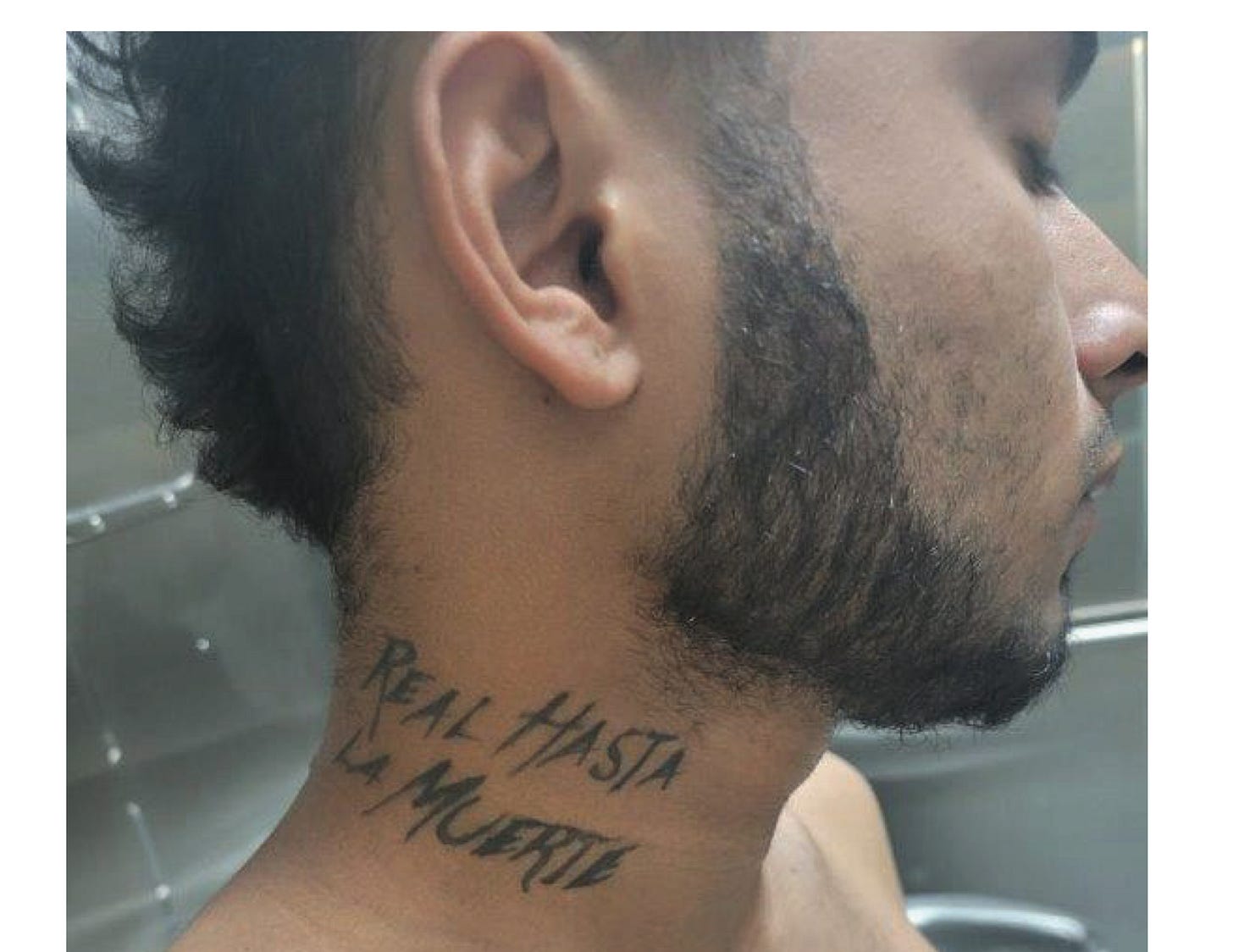

On March 3rd, Las Cruces Magistrate Judge Jose Cano (D) quietly resigned from the bench after three re-elections since 2011. On the same day, prosecutors were down the street in federal district court arguing that a recent arrestee, a Venezuelan national named Christhian Lopez-Ortega, 23, was a Tren de Aragua gang member and a flight risk.

The two men’s connection defies belief.

Christhian was first caught crossing the border at Eagle Pass in December, 2023, but was freed three days later— due to overcrowding. This year, three days before Judge Cano tendered his letter of resignation, the El Paso Homeland Security Office, responding to an anonymous tip, raided the judge’s Las Cruces home and found the gang member living in the judge’s guest cottage, or what the locals call a casita.

Homeland Security officers nabbed Lopez-Ortega with a bunch of guns (a felony), and the family closed ranks, claiming the guns were owned by the Judge’s daughter, April. The government’s April 8th motion for reconsideration drily reported, “The Defendant admitted that he knew it was illegal for him to possess firearms.”

According to federal filings, Judge Cano’s liberal wife Nancy came upon the young man working construction and hired him to replace a glass door and do a couple odd jobs around the house. After Lopez-Ortega was evicted from his apartment, Nancy invited him to live with the family, and began driving him to his immigration appointments and his construction gigs.

No good reason for inviting a 23-year-old gang member into the family appears in any of the reports, leaving ample space for sordid speculation. Generously, the affluent middle-aged mom may have thought she just was helping “reform” the career gangster.

Investigators discovered some clues in Lopez-Ortega’s text messages. He called Nancy his “patrona,” which I believe is Venezuelan for “sugar momma.” One unidentified amigo asked Lopez-Ortega to get him “two grenades.” Another texted him a grisly murder scene photo showing decapitated victims with their hands cut off, a gruesome photo attached in full to Homeland’s motion, but which I will not reproduce here in close-up.

Troublingly, the local federal Magistrate judge overruled Lopez-Ortega’s bond, rebuffing federal prosecutors and saying something like, “I’m sure he’s okay if he’s living with Judge Cano.” The federal judge even tried to remit the gang member back into Nancy Cano’s custody.

That prompted the government’s attorneys to file an emergency motion for reconsideration, which has not yet been set for hearing.

🔥 This story involves two judges. The first, a sitting state judge embroiled in what appears at minimum to be a non-traditional relationship with a member of a designated terrorist organization, an illegal, gang-tattooed alien the Cano family shared everything with including their firearms, and a second local federal judge who in open court said he would release the man because he was friends with the first judge.

If this story came from Venezuela, it would surprise no one. But it’s from New Mexico.

This troubling tale has created a certain amount of buzz in local and social media, percolating just below corporate media’s veneered surface. If we had a functioning media, which we obviously do not, they would tell us how historically, the corruption of local judiciary is one of the first and most critical steps that cartel-style organizations take when consolidating soft territorial control.

Cartels are cagey, sly, and experienced. They don’t roll into a new area in hummers holding assault rifles. They quietly assimilate and get a read on the local judicial and law enforcement arena. Then they deploy a carrot and stick approach. They offer sweet bribes, called “plata” (silver), sometimes cloaked as gifts or brokered with third parties. And, for judges who don’t take bribes, they offer quiet threats, called “plomo” (lead): you don’t want to deny bail on a TdA hermano.

Plata or plomo. Silver or lead.

The cartels realize that the judicial bench is the choke point. There are only a handful of judges in each locale, so controlling even one through plato or plomo makes a measurable difference. Control the judiciary, and you effectively control law enforcement. It’s not just a cartel thing, it’s an organized crime tactic. You can find similar examples in the 1980’s mafia and the 1930’s Chicago mobsters.

The cartels are just the tactic’s most recent incarnation.

🔥 In other words, this suppressed story is narrative dynamite. It is a much more threatening example than that MS-13 moron down in CECOT. Here, we have a U.S. judge literally living under the same roof with a violent, illegal alien gang member (if requests for grenades and snuff photos of gang killings aren’t enough evidence of violent inclination, then I don’t know what to tell you). And we see a second judge in a completely different courthouse running cover for the first judge.

But here, the media could care less about Christhian Lopez-Garcia’s deportation battle.

Here’s a link to the government’s motion for reconsideration, but note that some of the final attachments are graphic.

Thus, we begin to see the abolition of the judiciary. And over the weekend, the Supreme Court made things much, much, worse. Or more interesting, depending how you look at it.

⚖️⚖️⚖️

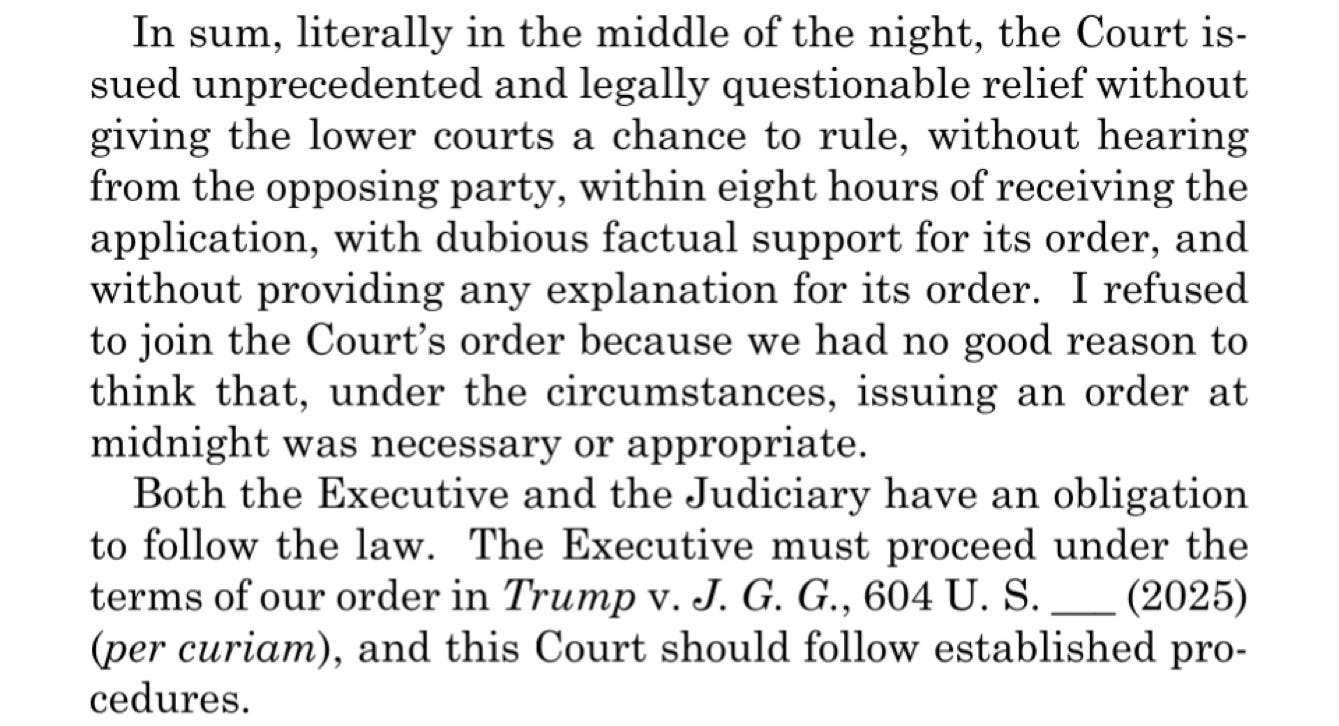

In another record-shattering development, the New York Times ran a non-story, a story that was no story at all, topped with an intentionally neutral headline, and just reprinting a Supreme Court dissent in full. The headline only said, “Read Justice Samuel Alito’s Dissent in the Alien Enemies Act Case.” The ‘story,’ if you can call it that, was a single sentence. All the Times could manage to eke out was, “Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. wrote that the Supreme Court’s decision to block the Trump administration from deporting Venezuelan migrants under a wartime law was premature.”

Hardly. He said a lot more than that. At midnight on Saturday night, Justice Samuel Alito, joined by Justice Thomas, filed a scorcher of a dissent. It responded to a previous midnight decision in AARP vs. Trump, in which the seven other justices had joined on an emergency basis. Justice Alito’s dissent was white-hot. Here’s how it concluded:

You can argue that the Supremes were just following a previously established pattern: they generally don’t rule on appeals from TRO’s, but instead have been waiting for the lower court to first enter a reasoned decision on a preliminary injunction. So far, those cases have all wound up going Trump’s way, albeit after a short period of discomfort. The bigger problem is that lower courts seem to be taking advantage of this prudish restraint and are pushing the outer limits of what’s appropriate or legal to include in a temporary restraining order.

In any case, the Supreme Court’s Friday night order included this remarkable line: “The Government is directed not to remove any member of the putative class of detainees from the United States until further order of this Court.” Giving the Court the benefit of the doubt, it appeared to be attempting to avoid another Judge Boasberg-style mess where Tom Homan just puts the detained plaintiffs on the next plane to El Salvador. Sorry, judge, they’re already gone.

But other commenters saw it as the Supreme Court indefinitely shutting down a whole class of deportations, in a case where they probably lacked jurisdiction, and where the so-called ‘class’ never should have existed to start with. I think everything is going to work out fine, and I don’t want to waste time with the details of yet more leftwing lawfare that is going nowhere.

But this snap, midnight Supreme Court decision put what could be the final polish on a galaxy-sized issue that nobody has dared to consider so far.

⚖️ The U.S. Constitution mentions an archaic, oddly-named privilege called the writ of habeas corpus in its Article I, Section 9, Clause 2. Let’s read Clause 2 together:

“The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.”

The ‘privilege’ of the writ of habeas corpus traces its storied lineage back to the Magna Carta. It gives due process rights to anyone detained by the government and gives anyone jailed an in-person court hearing. It also bars indefinite detention. In short, the government can’t just disappear people, so some historians call it the “Great Writ of Liberty.”

Famously or infamously, depending on your point of view, President Lincoln partially suspended the writ in certain key military corridors during the Civil War. It led to a showdown with the Supreme Court in a famous case called Ex parte Merryman. Merryman, who lived in Maryland, was arrested by the U.S. military in May, 1861, for treasonously burning railroad bridges to block Union troops and for recruiting Confederate forces.

Chief Justice Taney found Lincoln’s suspension of the writ to be illegal, holding (quite reasonably) that since Clause 2 appears in Article I, it’s a power held by Congress, not by the Executive Branch.

But the decision did not settle anything; just the opposite. Lincoln (also famously or infamously) ignored the Court’s order. Chief Justice Taney had ordered the military to immediately release John Merryman and coughed up a blistering written opinion, but Lincoln never flinched. He kept Mr. Merryman in chokey and asked Congress to approve the writ’s suspension retroactively— which they did, two years later in 1863, in the Habeus Corpus Suspension Act.

Lincoln enjoyed full public support —the “will of the people”— but modern critics find the Merryman kerfluffle to be Lincoln’s original dictatorial sin. Still, they usually fail to grapple with the fact that Congress subsequently endorsed it — two branches against one.

Merryman never settled the dispute. First, Justice Taney acted alone, in his capacity as a circuit judge, and not for the entire Court. So his decision has no precedential power. Second, Congress blessed Lincoln’s suspension in its 1863 Act. Third, in the years following Merryman, the Supreme Court has carefully danced around the authority issue and has never formally held that a sitting president cannot suspend the writ without Congress.

⚖️ To me, it looks a whole lot like President Trump has been preparing a path to argue for suspending habeas corpus.

First, and most importantly, right out of the gate President Trump issued an executive order declaring mass illegal immigration was an ‘invasion.’ Invasion is one of only two constitutional grounds for suspending the writ. Second, Trump has invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 —the Act at the heart of these key cases— which invokes precedent for wartime-style legal authority over foreign nationals, bypassing peacetime due process protections.

In J.G.G. v. Trump, the Boasberg case, the administration proceeded with deportations despite a temporary restraining order, foreshadowing Lincoln-style defiance. It wasn’t actual defiance, not really, since the Administration argues it did comply with Boasberg’s TRO. But it was nevertheless just short of defiance, since Judge Boasberg clearly disagrees.

Last week, the DC Circuit stayed Boasberg’s contempt order, defusing an imminent constitutional crisis at the last minute.

Third, and maybe most importantly, everything we can see is barreling toward galvanized public support for suspending the writ. Trump and his allies have consistently described the crisis as unlawful judges defying the will of the people —just as in Lincoln’s day— and interfering with the President’s electoral mandate to remove foreign terrorists and cartel gangs from American shores.

In about twenty different ways, Trump has recently said things like, “I’m trying to protect the country—but judges are protecting criminals.”

Indeed, it is difficult to see how Trump can possibly remove up to 20 million illegal immigrants —fulfilling his campaign promise— if each illegal gets a court hearing. Removal at scale is impossible unless one of two things happens: either a massive, rapid expansion of the legal system, which is unlikely to say the least, or removal of the judicial bottleneck.

Our existing immigration system wasn’t built for mass enforcement— it’s built for case-by-case adjudication.

⚖️ Here’s where things get spicy. Trump, citing judges making it impossible for him to fulfill his mass deportation promises, could next ask Congress to authorize suspension of the writ in a continuing resolution, which circumvents the Senate filibuster. (Continuing resolutions are short-term funding bills that let the federal government stay open.)

If the Continuing Resolution also agreed that America is currently under invasion, then two branches would be lined up against one, and the Supreme Court would find it very difficult to undo. Even Justice Taney found that Congress can legally suspend the writ, so Congressional delegation of that authority to the President in a CR would be constitutionally sound.

And the Supreme Court has always deferred to the other branches over things like declarations of emergency, war, or invasions, calling those political questions rather than legal issues.

Once again we see the outlines of a carefully considered plan. One of Trump’s first moves was to declare an invasion, and to declare cartels to be foreign terrorist organizations, which put the Alien Enemies Act on the chessboard, framed the problem in military terms, and teed up an eventual showdown over the writ. Trump’s team must have known they’d face these due process problems in carrying out the mass deportation plan.

Critically, the Courts could avoid this appalling scenario by crafting smart, balanced legal opinions that help the Administration accomplish its objectives without hamstringing it with micromanaged due process concerns. For instance, they could hold that non-citizens caught near the border during a declared invasion have strictly limited procedural rights, especially if prosecuted under the Alien Enemies Act or other federal immigration statutes.

Or, courts could invoke the political question doctrine, and hold that the determination of “invasion” is the province of Congress and the Executive, not the courts. Instead of requiring full due process for illegal terrorists, they could order reporting requirements, time limits, and narrow targeting. Or they could define the limits of emergency Executive powers and require Congress to ratify Trump’s emergency policies within a certain period of time.

But instead, the Courts are walking right into the trap. In their institutional vanity, procedural rigidity, and Trump derangement, the courts are doing exactly what executive strategists want them to do: lean hard into due process formalism, telegraph hostility, and issue sweeping rulings that look like they’re siding with gang-affiliated aliens over national security.

It practically invites defiance. It lets Trump rightfully say, Look, I didn’t want to ignore the courts—but I have no choice. They’ve made the country ungovernable.

Trump is forcing the courts into a clear choice: cooperate or become irrelevant.

⚖️ And so we return to Justice Alito’s scathing dissent, which reads like a manifesto for suspension of the writ. The logic and tone of Alito’s dissent make it clear that he sees judicial overreach as the true constitutional crisis, rather than executive enforcement.

When Alito wrote, “Both the Executive and the Judiciary have an obligation to follow the law,” he was saying that when the Executive uses legal tools like the Alien Enemies Act and constitutional powers during a crisis, the Court’s role is to tread lightly.

By pointing out the absurdity of class-wide habeas, and the procedural circus of midnight TROs based on speculative harms, Alito implictly argued that the writ is being abused by the courts— which sets the stage for suspending it entirely.

Alito’s dissent rang with echoes of the Civil War-era logic of necessity that Lincoln invoked in Ex parte Merryman. Alito signaled that, if the President acts lawfully under an invasion theory, the courts should not interfere with procedural technicalities. His dissent’s strong language undermined the legitimacy of judicial interference with mass enforcement, fueled public sympathy against detainees by focusing on legal overreach and lack of any rationale explanation, and created a quotable moral and legal groundwork to argue that: the judiciary left us no choice. The writ is now suspended.

Neither the Obama nor Bush administrations faced the kind of judicial micromanagement over deportations that Trump has encountered, and no court issued a nationwide TRO halting those presidents’ deportation programs, much less midnight orders eviscerating mass enforcement.

⚖️ At bottom, this lawyer sees a timid, reactive Supreme Court desperately trying to walk an increasingly thin line between endorsing the Administration’s aggressive immigration enforcement and maintaining judicial credibility. But that timidity is walking the country into uncharted constitutional waters.

In 2018, Chief Justice Roberts wrote an opinion in Trump v. Hawaii, upholding Trump’s “muslim travel ban.” But in it, he sharply criticized the court’s decision in Korematsu, which upheld FDR’s internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. That decision was never overturned, but Roberts called it a stain on the Constitution. FDR didn’t need to suspend the writ because the courts let him conduct de facto mass detention.

This time, unlike in FDR’s day, the courts aren’t letting Trump conduct mass deportations. Justice Roberts seems obsessed with not getting on history’s wrong side by endorsing another Korematsu. But in undermining the Executive’s core constitutional function to defend the borders, he is also undermining the Court’s own legitimacy, by issuing hasty, unsustainable rulings with no constitutional compass or even a plan.

In 1942, executive overreach was the problem. In 2025, it may be judicial overreach. This time, the courts aren’t letting the executive function, and that may prove far more dangerous than the Court’s passive deference of 1944.

The battle is far from over. Whatever happens, it’s going to make more history. And it definitely won’t be boring.

Have a magnificent Monday! We’ll be back tomorrow morning with a serving of all the essential news and a side dish of compelling commentary.

Don’t race off! We cannot do it alone. Consider joining up with C&C to help move the nation’s needle and change minds. I could sure use your help getting the truth out and spreading optimism and hope, if you can: ☕ Learn How to Get Involved 🦠

How to Donate to Coffee & Covid

Twitter: jchilders98.

Truth Social: jchilders98.

MeWe: mewe.com/i/coffee_and_covid.

Telegram: t.me/coffeecovidnews

C&C Swag! www.shopcoffeeandcovid.com

Bill Clinton: 12.3 million deportations - 0 injunctions

George W. Bush: 10.3 million deportations - 0 injunctions

Barack Obama: 5.3 million deportations - 0 injunctions

Donald Trump: 100 thousand deportations - 30 injunctions

To me, it looks a whole lot like President Trump has been preparing a path to argue for suspending habeas corpus.

Jeff, that is precisely what it looks like to me. Terrorists do not get habeus corpus. They get deportation. Anywhere but here.